The Jewish in Rome

The Jews in the capital of Italy are perhaps the oldest Romans of all. They have been settled in the same ancient neighborhoods in the heart of the Eternal City for 2000 years, making their homes in the former ghetto, in Trastevere, and on both sides of the Tiber River where it is crossed by the Ponte Fabricio or Ponte Quattro Capi. Not only one of the oldest communities of the peninsula, Roman Jewry also represents one of the most important, lively, and deeply rooted communities today, with its own dialect containing Hebrew words and particular culinary tradition. This 2000-year-old homeland, without equal with the exception of Israel, preserves numerous monuments dating from all periods, from the Jewish catacombs or the Ostia Antica Synagogue to the Grand Temple constructed at the beginning of the twentieth century on the location of the former ghetto. A visit to Jewish Rome merits at least five days. In this Christian capital, the rich remains of Jewish history proper are augmented by many things that attest to papal policy regarding the Jews. Some for the better and most for the worst, these physical records conditioned Jewish life in Rome -if not in the west as a whole.

The Jewish ghetto History

The quarter where the Jews were forced to reside for three centuries until 1870 is at the center of the Italian capital, between the Largo Argentina, the Capitoline, and the Tiber. Almost nothing remains of the stifling, cramped streets of the old ghetto, which was destroyed, sanitized, and reconstructed in the first years of the twentieth century. The neighboring narrow streets, such as Via della Reginella or the beginning of Via Sant’Angelo in Pescheria, give an idea of what the lives of the Jews in the city were like for three hundred years.

The ghetto was established on 14 July 1555 by Paul IV with the Cum Nimis Absurdum edict: “Because it is absurd and inconvenient to the utmost degree that Jews, condemned for their faults by God to eternal slavery, can with the excuse of being protected by Christian love, be tolerated living among us…” The walls of the ghetto were constructed in less than three months. In 1816, the ghetto occupied some 325000 square feet of which 250000 square feet were inhabitable. More than 5000 persons were living there when the walls fell little more than a century ago. This one one of the highest population density in the capital, and in a disease-prone district inundated at each swelling of the Tiber. The buildings pushed heavenward, up to seven or eight stories high, and more and more overpopulated. Buildings collapses were frequent. “This entire ensemble of persecutions had fallen into disuse, but with the death of Pius VII [in 1823] everything began again: the Jews were shut up in their ghetto.

Portico D’ottavia

Portico d’Ottavia, constructed by Cecilius Metella in 146 B.C.E. remains one of the symbolic places of the former Roman ghetto. The remains of the fluted columns rise from among the enormous paving stones surrounding the large Temple of Juno on Via del Portico d’Ottavia.

Restaurants set up their sidewalk tables from which the regulars take in the fresh air. This portal marks one of the five former entrances to this forced residential quarter. It was customarily barred at night with a great iron chain.

The Piazza delle Cinque Scole surrounds a fountain by Giacomo della Porta (erected in 1591, rebuilt in 1930) commemorating the five synagogues of the former ghetto (Catalana, Castigliana, Tempio, Siciliana, and Nova).

These were all located in a single building that has since vanished but which was located on the present-day square at number 37. The current building is constructed on the site of the former Platea Judea, or “grand square”, divided into two halves by the ghetto wall, which was the intersection of two ancient thoroughfares of the Jewish quarter, Via Pescaria and Via Rua.

It was in the Platea Judea, at once inside and outside the ghetto, that the economic activities permitted to the Jews of Rome took place. These activities included trade in old clothing, used goods, and some artisanal work. In periods of tolerance these stalls were permitted to open on Sunday and the villagers who had come to the city and did not want to lose a day would come her to make their purchases.

The Piazza delle Cinque Scole, with its many shops, remains the heart of the quarter. Be sure not to miss a pasticceria called Boccione, which sells cakes typical of the Roman-Jewish tradition such as its extraordinary cheesecake made from ricotta.

Menorah, a nearby bookstore, is well stocked with both old and new books on Judaism in Italian, French and English.

Heading back up this narrow, shadowy street toward the Piazza Mattei, with its magnificent “tortoise” fountain constructed in 1581-84, it is possible to get an idea of what the ghetto was like back in those ancient times.

——————————————————————-

Important place not to miss in the Jewish ghetto of Rome

Stolpersteine The “pietre d’inciampo”, the special cobblestones in Rome

While strolling through the streets of Rome, one can come across these very special cobblestones. A shiny brass plaque covers the stone. These stand out among all the other cobblestones (called “sanpietrini” in Rome) creating a metaphorical ‘stumble’ in our mind. This is why they are called “d’inciampo”. It is the Italian translation for “stumble”. Come to Rome and take one of Tours. While walking around the Eternal City, we’ll make sure to show you the “pietre d’inciampo”, the special cobblestones in Rome.

While strolling through the streets of Rome, especially in the Jewish ghetto area, one can come across these very special cobblestones called “pietre d’inciampo”. The typical roman cobblestones are covered with a shiny brass plaque that makes these paving stones, stand out from the rest. They all have an inscription with the name of the people who have suffered persecutions and deportations. Their birth date and the location to which they were deported, if known.

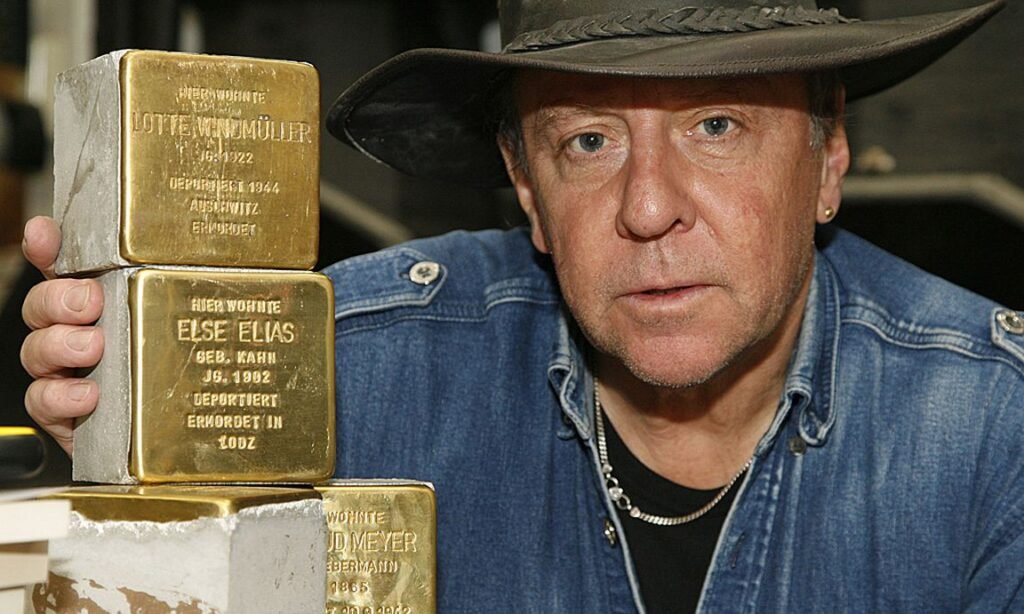

The “pietre d’inciampo”, the special cobblestones in Rome the, are also known as Stolpersteine. This means stumbling stones. They were installed from 1995 on the roads all over Europe. It is the craft of German artist Gunter Demnig.

A discreet way to put his project into practice was to create these special cobblestones. A stone that becomes a monument without emerging from the earth but sinking into it. It does not impose itself to the observer but is stumbled upon casually. On the shiny brass surface, each “pietra d’inciampo” bears the name of a victim of persecution, the place where he or she lived, or where they were deported. A beautiful, graceful and powerful way to celebrate the victims of the Holocaust.

There are over 22,000 stones in Germany, Austria, Hungary, Ukraine, Czechoslovakia, Poland, the Netherlands and in Italy. In Rome, in particular, there are more than 300 “pietre d’inciampo”. These create an unusual memory map to remember those who suffered persecutions.

Gunter Demnig decided to dedicate his life and work to the memory of all deportees worldwide.

——————————————————————-

Via della Reginella

The blocks of buildings situated between Via Reginella and Via Sant’Ambrogio became part of the Jewish quarter when Pope Leon XII designed to enlarge it a little in 1823.

Completely on the other side of the former Jewish quarter, and heading in the direction of the Tiber and the Grand Temple, stands the small church of San Gregorio all Divina Pietà, constructed in the eighteenth century opposite one of the ghetto gates.

Its facade features an inscription in Latin and Hebrew citing the prophet Isaiah speaking “to those rebellious people who act according to ideas in a way which isn’t good, to those people who continually provoke my anger”. This was one of the places where each Sunday, representatives of the Jewish community were obliged to listen to the Catholic Mass.

In Via della Reginella there are several cobblestones. precisely at the number 9,10,19 and 27

——————————————————————-

Tortoise Fountains

In Old Jewish Quarter, surrounded by the palaces that once belonged to the noble Mattei family who gave the square its name, stands one of the most beautiful fountains in Rome. The Fountain of the Turtles was built between 1581 and 1588 on a project by Giacomo della Porta (1533-1602).

The history of the fountain comes from a romantic fable. According to legend, Duke Mattei, a gambler, lost his entire family fortune in one fell swoop. The future father-in-law, therefore, refused to give him his daughter in marriage. In response, the duke had this magnificent artwork built in a single night. The following day he invited his betrothed and her father to the palace to show them the fountain. He exclaimed: “This is what a penniless Mattei can accomplish in a few hours!”. In memory of the episode, he had the window from which they looked out to admire the fountain walled up.

Among rich decorations in polychrome marble, four bronze children ride dolphins on shell-shaped tanks sculpted by Florentine Taddeo Landini (1550-1596). From 1658, they “play” with the turtles, added to the fountain by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

The Grand Temple

The zinc dome of the Grand Temple rises 151 feet above the street and can be seen from anywhere in Rome among the other baroque domes of the many churches in the Eternal City. It is easily recognized by its square shape. Constructed between 1901 and 1904, hardly more than thirty years after the closing of the ghetto, the Grand Temple celebrates the Italian Jews and their extraordinary integration.

The style of the Temple is oriental, though some have ironically described it as neo-Babylonian.

——————————————————————-

Jewish Museum of Rome

The facade is adorned wit palms and has three large windows. Near its top, the building features a tympanum decorated with the Tablets of the Law, above which stands a seven-branched menorah. The interior of the main hall is sumptuous, with marble columns in an oriental style. The aron, above the steps of a platform at the end of the nave, evokes the altar of a church, like many of the synagogues constructed just after the Jews’ emancipation. Abundant light pours in through the large liberty-style windows. The interior of the large dome is decorated with oriental-style paintings (palms and starry sky) by Annibale Brugnoli and Domenico Bruschi. In the halls of the Grand Temple many of the objects historically used in the five synagogues of the former ghetto have been assembled and are on display.

Especially noteworthy are the magnificent marble-columned aronot from the Siciliana Synagogue of 1586 and that of the Castigliana Synagogue of 1642. The Spanish Temple, occupying since 1932 a large part of the Grand Temple, perpetuates the tradition of Jews who came from the Iberian Peninsula, while the majority of the services are now in Italian. The hall with its aron facing the tevah evokes the atmosphere of the former Roman synagogue that has since disappeared. The Jewish Museum occupies one of the wings of the Grand Temple. Numerous silver religious objects, circumcision chairs, candelabras, fabrics, and manuscripts, including three volumes of poems in Judeo-Roman by Crescenzo del Monte (1868-1935), are on display in two vast rooms.

——————————————————————-

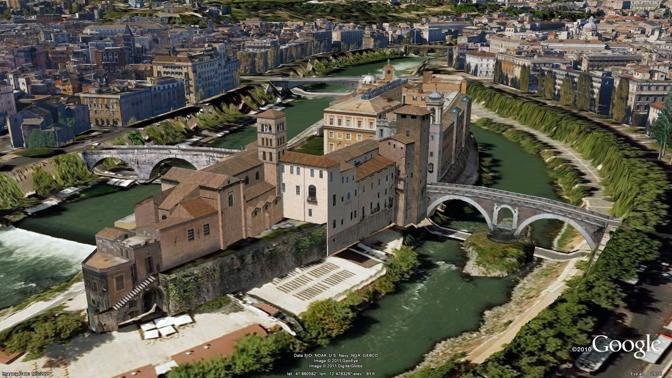

Tiber Island

The only island in the Tiber River as it snakes through Rome, Tiber Island was consecrated by the ancient Romans to Aesculapius, the god of medicine. Since the Middle Ages, it has been the site of the hospices or hospitals. The island links the Jewish quarter on either side of the river; thus in the eleventh century both the Ponte Fabricio and the Ponte Quattro Capi were alternately called the Pons Judeorum. In 1870 the confraternities of the former ghetto settled here in order to create aid organizations for the newly emancipated Jews. One one side of the island’s central street facing upstream stand the Israelite hospital and the Panzieri-Fatucci oratory, called the Tempio dei Giovanni. The nineteenth century wooden aron of the oratory originally came from the five synagogues. The brightly colored stained-glass windows representing Jewish holidays were completed in 1988.